Whedon! Acker! Denisof! Shakespeare!

Of Gods and Men

Jayson Stark on Albert Pujols' monumental World Series Game 3, in which Pujols became only the third player in baseball history to hit three home runs in a World Series game (following Babe Ruth, who did it twice, and Reggie Jackson).

Robert Christgau's excellent Rock&Roll& piece on Jay-Z and his reconsidered Consumer Guide blurbs for Reasonable Doubt and The Black Album.

Adam Cook on Soderbergh's Contagion, which he terms a "a masterpiece pertinent to current day but guaranteed to become increasingly so as time goes on."

TIME's Richard Stengel and Mark Halperin interview the terrifying Rick Perry.

Jayson Stark on Albert Pujols' monumental World Series Game 3, in which Pujols became only the third player in baseball history to hit three home runs in a World Series game (following Babe Ruth, who did it twice, and Reggie Jackson).

Robert Christgau's excellent Rock&Roll& piece on Jay-Z and his reconsidered Consumer Guide blurbs for Reasonable Doubt and The Black Album.

Adam Cook on Soderbergh's Contagion, which he terms a "a masterpiece pertinent to current day but guaranteed to become increasingly so as time goes on."

TIME's Richard Stengel and Mark Halperin interview the terrifying Rick Perry.

The Limits of Control

In his Cannes coverage for The A.V. Club, Mike D'Angelo wrote:

Would people even know what to make of Melancholia were it not public knowledge that Von Trier has been suffering from clinical depression for the past few years? (I guess maybe the title might be a wee clue.) More to the point, is it possible to “enjoy” it—whatever that word might mean in this context—if depression is something that you fundamentally don’t understand?

D'Angelo's first point is rather slippery, prompting as it does the question of how many other significant recent films "require" extra-textual information in order to be fully appreciated. Does, for instance, the amazing story of This Is Not a Film being smuggled from Iran to Cannes in a loaf of bread amplify one's admiration for Panahi's accomplishment? Is some knowledge of the autobiographical nature of The Tree of Life necessary to "get" Malick's film? I will return to this point a little later...

As for the second question quoted above, I would contend that this "fundamental" lack of understanding is precisely what von Trier has in mind.

Melancholia is bipartite in its structure, with rhyming halves named for the sisters Justine and Claire. The first half focuses on the clinically depressed Justine (an astonishing return to peak form from Kirsten Dunst), as she navigates the hell that is other people on the night of her wedding reception. For those of us who can't "understand" Justine's (and von Trier's) condition, her turbulent, self-destructive behavior initially seems irrational. Her husband, Michael, (Alexander Skarsgard, light-years from True Blood's Eric) appears to be a nice, well-meaning guy; her wealthy sister, Claire (Charlotte Gainsbourg), and brother-in-law, John (Kiefer Sutherland), are going all out for her reception, hosted at their country mansion/luxury golf resort; her boss, Jack (Stellan Skarsgard), just gave her a raise from copywriter to art director at his advertising form. What's so bad about that?

This, in so many words, is what Claire and John persistently ask Justine, as she moodily retreats from the elaborately orchestrated reception. Justine responds in her own defense that she is trying: smiling, dancing, going through the motions of the just-married. However, even for those of us who can't easily empathize with Justine's emotional state, there are subtle signs that suggest (at least partly) the source of her anxiety: a suffocating lack of control over the decisions that shape her life. When Michael surprises her with a photograph of the land he has secretly signed off on for them to make their home, the sweetness of the gesture, and of his apparent demeanor, obscures the fact that he seemingly hasn't consulted his bride on such a major move. Likewise, Claire and John have meticulously planned out the wedding reception (and, as John repeatedly notes, spent a small fortune on it), leaving Justine little room for input. And in Jack's congratulatory announcement of Justine's promotion, via a toast speech to the newlyweds, there is no question mark regarding Justine's new position--just a forceful exclamation point.

Still, when by the end of the night, Justine's marriage has essentially dissolved, it remains almost incomprehensible (for most of us) how things could have gone so bad so fast--and yet this first-half conclusion feels at least as brutally inevitable as it does baffling. Justine says in parting to Michael that he couldn't have truly expected it to have turned out any other way. He doesn't argue with this point.

The second ("Claire") half of Melancholia mirrors the opening ("Justine") half in this feeling of inexorable doom. For viewers who personally can't understand clinical depression, this section presents an extreme scenario of "situational" depression with which the audience will certainly relate. It is here that the film explicitly morphs into what J. Hoberman calls "Ibsen as science-fiction." A planet, "Melancholia," has gone off its axis (or something) and is headed toward Earth. The scientifically-minded John predicts that it will safely fly by, and Claire tries to buy into his logic--much the same way Justine tries to smile and feign happiness in the film's first half--but never fully accepts his contention, and becomes increasingly hysterical. It soon becomes clear that John is wrong, and that no amount of rationalizing or wishful thinking will prevent what is soon to come.

As much as the rapidly approaching Melancholia itself (and the consequent destruction of Earth), Claire is overwhelmed and terrified by her sudden helplessness. At one point, she tries to get in her car to drive from her country estate into the village, as if being among a larger group of people might somehow stave off disaster. (This scene speaks to the disturbing claustrophobia of the film's second half, wherein the social dynamic of the first half is contrasted by its absence; the audience can only wonder how the rest of the world is responding to, or coping with, this doomsday moment.) Meanwhile, Justine, crashing with Claire and John after her wedding night meltdown, takes a perverse delight in the end of the world; perhaps now all the unsympathetic people who endlessly tell her to just "be happy" will know what it's like to feel the walls violently closing in.

Circling back to D'Angelo's first question: Justine and Claire--and the halves of the film titled for each sister--seem to function as, respectively, the director-surrogate and audience-surrogate. The intense discourse inspired by these concentric relationships gets us somewhere close to the "heart" of the film. So, yes, an understanding of, not the experience of clinical depression (it's like watching a rogue planet travel through the sky en route to obliterating the one we live on, remember?), but of Lars von Trier's much-publicized medical history does add a rich extra layer to one's engagement with Melancholia.

A familiarity with von Trier's filmography doesn't hurt either, as the director is returning critically to key elements of his earlier work. The first half echoes Bess and Jan's wedding in Breaking the Waves, but in the new film the setting is distinctly upper-crust, where in the earlier case it is much more modest (perhaps a reflection on how far von Trier himself has moved beyond his down-and-dirty Dogme 95 days). Also, where Bess is giddily eager to consummate her marriage to Jan, Justine refuses to have sex with Michael--and when she sleeps with another man, it's decidedly not at her husband's desperate insistence. When towards the end of Melancholia, Justine matter-of-factly tells Claire that "life on Earth is evil," it clearly calls to mind Dogville's incendiary final act, but here the context is more existential anxiety than theological, Old Testament wrath. And like Antichrist (also co-starring the terrific Gainsbourg), von Trier's latest is, of course, a deeply personal statement on depression ostensibly packaged as a genre exercise: last time "horror," this time "sci-fi."

But where Antichrist is fatally muddled both in conception and execution, Melancholia is von Trier's most fully-realized film since Dogville. If it requires some contextual leg-work on the part of the viewer, it's worth it; if it's not a masterpiece, it's close.

In his Cannes coverage for The A.V. Club, Mike D'Angelo wrote:

Would people even know what to make of Melancholia were it not public knowledge that Von Trier has been suffering from clinical depression for the past few years? (I guess maybe the title might be a wee clue.) More to the point, is it possible to “enjoy” it—whatever that word might mean in this context—if depression is something that you fundamentally don’t understand?

D'Angelo's first point is rather slippery, prompting as it does the question of how many other significant recent films "require" extra-textual information in order to be fully appreciated. Does, for instance, the amazing story of This Is Not a Film being smuggled from Iran to Cannes in a loaf of bread amplify one's admiration for Panahi's accomplishment? Is some knowledge of the autobiographical nature of The Tree of Life necessary to "get" Malick's film? I will return to this point a little later...

As for the second question quoted above, I would contend that this "fundamental" lack of understanding is precisely what von Trier has in mind.

Melancholia is bipartite in its structure, with rhyming halves named for the sisters Justine and Claire. The first half focuses on the clinically depressed Justine (an astonishing return to peak form from Kirsten Dunst), as she navigates the hell that is other people on the night of her wedding reception. For those of us who can't "understand" Justine's (and von Trier's) condition, her turbulent, self-destructive behavior initially seems irrational. Her husband, Michael, (Alexander Skarsgard, light-years from True Blood's Eric) appears to be a nice, well-meaning guy; her wealthy sister, Claire (Charlotte Gainsbourg), and brother-in-law, John (Kiefer Sutherland), are going all out for her reception, hosted at their country mansion/luxury golf resort; her boss, Jack (Stellan Skarsgard), just gave her a raise from copywriter to art director at his advertising form. What's so bad about that?

This, in so many words, is what Claire and John persistently ask Justine, as she moodily retreats from the elaborately orchestrated reception. Justine responds in her own defense that she is trying: smiling, dancing, going through the motions of the just-married. However, even for those of us who can't easily empathize with Justine's emotional state, there are subtle signs that suggest (at least partly) the source of her anxiety: a suffocating lack of control over the decisions that shape her life. When Michael surprises her with a photograph of the land he has secretly signed off on for them to make their home, the sweetness of the gesture, and of his apparent demeanor, obscures the fact that he seemingly hasn't consulted his bride on such a major move. Likewise, Claire and John have meticulously planned out the wedding reception (and, as John repeatedly notes, spent a small fortune on it), leaving Justine little room for input. And in Jack's congratulatory announcement of Justine's promotion, via a toast speech to the newlyweds, there is no question mark regarding Justine's new position--just a forceful exclamation point.

Still, when by the end of the night, Justine's marriage has essentially dissolved, it remains almost incomprehensible (for most of us) how things could have gone so bad so fast--and yet this first-half conclusion feels at least as brutally inevitable as it does baffling. Justine says in parting to Michael that he couldn't have truly expected it to have turned out any other way. He doesn't argue with this point.

The second ("Claire") half of Melancholia mirrors the opening ("Justine") half in this feeling of inexorable doom. For viewers who personally can't understand clinical depression, this section presents an extreme scenario of "situational" depression with which the audience will certainly relate. It is here that the film explicitly morphs into what J. Hoberman calls "Ibsen as science-fiction." A planet, "Melancholia," has gone off its axis (or something) and is headed toward Earth. The scientifically-minded John predicts that it will safely fly by, and Claire tries to buy into his logic--much the same way Justine tries to smile and feign happiness in the film's first half--but never fully accepts his contention, and becomes increasingly hysterical. It soon becomes clear that John is wrong, and that no amount of rationalizing or wishful thinking will prevent what is soon to come.

As much as the rapidly approaching Melancholia itself (and the consequent destruction of Earth), Claire is overwhelmed and terrified by her sudden helplessness. At one point, she tries to get in her car to drive from her country estate into the village, as if being among a larger group of people might somehow stave off disaster. (This scene speaks to the disturbing claustrophobia of the film's second half, wherein the social dynamic of the first half is contrasted by its absence; the audience can only wonder how the rest of the world is responding to, or coping with, this doomsday moment.) Meanwhile, Justine, crashing with Claire and John after her wedding night meltdown, takes a perverse delight in the end of the world; perhaps now all the unsympathetic people who endlessly tell her to just "be happy" will know what it's like to feel the walls violently closing in.

Circling back to D'Angelo's first question: Justine and Claire--and the halves of the film titled for each sister--seem to function as, respectively, the director-surrogate and audience-surrogate. The intense discourse inspired by these concentric relationships gets us somewhere close to the "heart" of the film. So, yes, an understanding of, not the experience of clinical depression (it's like watching a rogue planet travel through the sky en route to obliterating the one we live on, remember?), but of Lars von Trier's much-publicized medical history does add a rich extra layer to one's engagement with Melancholia.

A familiarity with von Trier's filmography doesn't hurt either, as the director is returning critically to key elements of his earlier work. The first half echoes Bess and Jan's wedding in Breaking the Waves, but in the new film the setting is distinctly upper-crust, where in the earlier case it is much more modest (perhaps a reflection on how far von Trier himself has moved beyond his down-and-dirty Dogme 95 days). Also, where Bess is giddily eager to consummate her marriage to Jan, Justine refuses to have sex with Michael--and when she sleeps with another man, it's decidedly not at her husband's desperate insistence. When towards the end of Melancholia, Justine matter-of-factly tells Claire that "life on Earth is evil," it clearly calls to mind Dogville's incendiary final act, but here the context is more existential anxiety than theological, Old Testament wrath. And like Antichrist (also co-starring the terrific Gainsbourg), von Trier's latest is, of course, a deeply personal statement on depression ostensibly packaged as a genre exercise: last time "horror," this time "sci-fi."

But where Antichrist is fatally muddled both in conception and execution, Melancholia is von Trier's most fully-realized film since Dogville. If it requires some contextual leg-work on the part of the viewer, it's worth it; if it's not a masterpiece, it's close.

VIFF: Best of the Fest

TOP TEN FILMS

01. This Is Not a Film (Panahi/Mirtahmasb)

02. Almayer's Folly (Akerman)

03. The Turin Horse (Tarr)

04. A Separation (Farhadi)

05. A Simple Life (Hui)

06. Year Without a Summer (Tan)

07. Martha Marcy May Marlene (Durkin)

08. Once Upon a Time in Anatolia (Ceylan)

09. Koran By Heart (Barker)

10. The Mill and the Cross (Majewski)

SPECIAL MENTION: Dreileben: Beats Being Dead (Petzold); Immmature (Yang, from A Time to Love); Open Verdict (Ho, from Quattro Hong Kong 2)

FEMALE PERFORMANCE (LEAD)

*Deannie Yip - A Simple Life

MALE PERFORMANCE (LEAD)

*Jafar Panahi - This Is Not a Film

FEMALE PERFORMANCE (SUPPORTING)

*Luna Zimic Mijovic - Dreileben

MALE PERFORMANCE (SUPPORTING)

*John Hawkes - Martha Marcy May Marlene

TOP TEN FILMS

01. This Is Not a Film (Panahi/Mirtahmasb)

02. Almayer's Folly (Akerman)

03. The Turin Horse (Tarr)

04. A Separation (Farhadi)

05. A Simple Life (Hui)

06. Year Without a Summer (Tan)

07. Martha Marcy May Marlene (Durkin)

08. Once Upon a Time in Anatolia (Ceylan)

09. Koran By Heart (Barker)

10. The Mill and the Cross (Majewski)

SPECIAL MENTION: Dreileben: Beats Being Dead (Petzold); Immmature (Yang, from A Time to Love); Open Verdict (Ho, from Quattro Hong Kong 2)

FEMALE PERFORMANCE (LEAD)

*Deannie Yip - A Simple Life

MALE PERFORMANCE (LEAD)

*Jafar Panahi - This Is Not a Film

FEMALE PERFORMANCE (SUPPORTING)

*Luna Zimic Mijovic - Dreileben

MALE PERFORMANCE (SUPPORTING)

*John Hawkes - Martha Marcy May Marlene

VIFF, Part 3: Days Go By

Are We Really So Far From a Madhouse? Li Honqi, director of last year's fest highlight Winter Vacation, returns with perhaps the most singularly bizarre musical tour documentary ever filmed. Working ostensibly within a format resistant to change or variation, Li follows the popular Chinese punk rock group P.K.14 as they drive across Mainland China, playing gigs and hanging out in hotel rooms. Right: this is, in essence, the content of every tour doc. But when the members of the band speak or perform, the audience instead hears an abrasive sonic collage of animal sounds and other strange, unidentifiable noise. Only when the group is on the road does Li pipe in their (excellent) music, as well as that of the folky spin-off Dear Eloise, creating a moody aural counterpoint to images of the Chinese highway-scape. These contemplative scenes contrast in fascinating ways with the weird energy of the animal-noise sequences. The combined result hangs together rather awkwardly and sometimes feels like radical experimentation purely for its own sake; and yet, at the same time, there is a nagging sense that something new, however cryptic, is being expressed here about the experience of a musical group trekking across the country together to perform their craft.

Le Havre Aki Kaurismaki's affectionate story of a middle-aged shoe-shiner in Normandy who aids a young African refugee wanted by the immigration authorities is charming and entirely likable. It also feels like Chicken Soup for the Aging Baby Boomer's soul. Kaurismaki and his charismatic protagonist (surname: Marx) wear their post-bohemian lefty heart on their sleeve, from the film's comically anti-authoritarian bent to nostalgic memories of Paris in the '60's. That's all fine and good, and if Le Havre's middlebrow charms translate into Oscar recognition, Kaurismaki is a decided step up from the Academy's typical taste in non-English language fare. But in bringing to the table issues of immediate relevance--illegal African migration in Europe, the Western healthcare crisis looming as the Boomer generation enters its golden years--Le Havre frustrates in its breezy reluctance to seriously consider these problems.

Martha Marcy May Marlene Sean Durkin's impressive debut feature centers on a young woman freshly escaped from a cult commune to her older sister's lake house, but is, more broadly, a dreamy meditation on the unshakability of the past within the human mind: how the people and places and moments we've known inevitably color our perception of the present--a sort of nightmare version of the Beatles' "In My Life," if you will. Elizabeth Olsen (younger sister to Mary-Kate and Ashley, but resembling in voice and presence the disaffected Scarlett Johansson of Ghost World and Lost In Translation) provides precisely the right kind of hazy, damaged, restrained yet emotionally raw turn as the titular heroine; if her performance had been remotely off the mark, Durkin's film simply wouldn't work. John Hawkes is likewise perfectly cast as the creepy, mercurial cult leader who haunts Martha's psyche. Speaking of Hawkes, Martha Marcy May Marlene follows last year's Winter's Bone in making a compelling argument for a new, reinvigorated American independent cinema that is refreshingly far from the quirky-snarky territory of Amerindies' past.

No One Killed Jessica For a viewer like myself, conditioned to the various incarnations of international festival-style (e.g., art-house) cinema, the most jarring moviegoing experience can often come in the form of an unabashedly commercial foreign movie. Raj Kumar Gupta's fictionalized take on the notorious Jessica Lall murder case feels formally alien to me--partly for the reason mentioned above and partly because my familiarity with Bollywood cinema is woefully limited--and my reaction should thus be taken with a grain of salt. The slick look and fast-paced rhythm of the film feel similar in ways to current Hollywood movies (in particular, stuff like Crash and Babel), but the on-the-nose writing, the histrionic style of acting, and the use of the weepy score registered as closer in spirit to the WWII-era Hollywood melodrama. Maybe this is how most Bollywood films feel? I really don't know. Still, I couldn't help but find the glossy form, with its oddly jokey script and abrupt use of dance and hard rock tunes on the soundtrack, disconcertingly crass in conjunction with the sad subject matter.

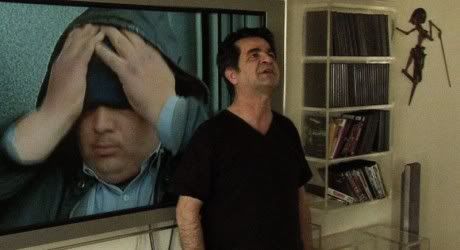

This Is Not a Film I was optimistically waiting for a truly galvanizing film-event at this year's VIFF--something along the lines of last year's Karamay or VIFF '07's Redacted, movies that (for this viewer anyway) felt instantly like game-changers. On the second-to-last day of this year's fest, that wish was granted in the form of Jafar Panahi and Mojtaba Mirahmasb's This Is Not a Film. Deceptively simple (in form and concept), the film (or non-film) is ultimately one of modern moviemaking's most thoughtful and provocative considerations of the deeply entangled, indeed inextricable personal and political dimensions of creating art. To be sure, Panahi's situation--sentenced to a six-year prison term that, in the film, he's attempting to appeal and banned from directing films for twenty years as a consequence of his involvement in the protests against Ahmadinejad's rigged reelection--is an extreme case, but the implications of This Is Not a Film extend beyond its Iranian context, as Panahi reflects on the director's relationship to, and "directing" of, his actors; the differences between "telling" a film and "making" one; and (necessarily indirectly) the moral-political responsibility inherent in making movies. Despite the dire circumstances of its creation, Panahi's film (with invaluable assistance by friend and fellow filmmaker Mirtahmasb) is as funny and vibrant as it is despairing and sad, and as triumphantly inventive as it is limited by its specific constraints. Brilliantly straddling the blurry line between spontaneous documentation and scripted narrative, This Is Not a Film is the very definition of a sui generis masterpiece.

The Turin Horse Setting aside issues of time-commitment (watching Satantango start to finish requires nearly one-third of a day), I would argue that Bela Tarr's supposed swansong is his most difficult film. Difficult--that is to say, it was considerably tougher for me to find a personal point-of-entry here than it was for Satantango, Werckmeister Harmonies, and Tarr's other earlier films--but not impenetrable, and far from unpleasurable. In fact, once I'd adapted to the fact that The Turin Horse's doom-laden narrative consists almost exclusively of a pattern of repetitions and occasional, ominously suggestive deviations (with these deviations essentially constituting the "arc")--a signature Tarr strategy here rigorously intensified to its apotheosis--I found the film to be among Tarr's most hypnotic and powerful. That said, I'm envious of Jonathan Rosenbaum, who mentions having attended three separate festival screenings of The Turin Horse in his superb Film Comment piece on the film. Of all the films I saw at this year's VIFF, this is the one I most wish I could've caught twice (or more). I'm already crossing my fingers that it will reappear in these parts sometime soon.

Are We Really So Far From a Madhouse? Li Honqi, director of last year's fest highlight Winter Vacation, returns with perhaps the most singularly bizarre musical tour documentary ever filmed. Working ostensibly within a format resistant to change or variation, Li follows the popular Chinese punk rock group P.K.14 as they drive across Mainland China, playing gigs and hanging out in hotel rooms. Right: this is, in essence, the content of every tour doc. But when the members of the band speak or perform, the audience instead hears an abrasive sonic collage of animal sounds and other strange, unidentifiable noise. Only when the group is on the road does Li pipe in their (excellent) music, as well as that of the folky spin-off Dear Eloise, creating a moody aural counterpoint to images of the Chinese highway-scape. These contemplative scenes contrast in fascinating ways with the weird energy of the animal-noise sequences. The combined result hangs together rather awkwardly and sometimes feels like radical experimentation purely for its own sake; and yet, at the same time, there is a nagging sense that something new, however cryptic, is being expressed here about the experience of a musical group trekking across the country together to perform their craft.

Le Havre Aki Kaurismaki's affectionate story of a middle-aged shoe-shiner in Normandy who aids a young African refugee wanted by the immigration authorities is charming and entirely likable. It also feels like Chicken Soup for the Aging Baby Boomer's soul. Kaurismaki and his charismatic protagonist (surname: Marx) wear their post-bohemian lefty heart on their sleeve, from the film's comically anti-authoritarian bent to nostalgic memories of Paris in the '60's. That's all fine and good, and if Le Havre's middlebrow charms translate into Oscar recognition, Kaurismaki is a decided step up from the Academy's typical taste in non-English language fare. But in bringing to the table issues of immediate relevance--illegal African migration in Europe, the Western healthcare crisis looming as the Boomer generation enters its golden years--Le Havre frustrates in its breezy reluctance to seriously consider these problems.

Martha Marcy May Marlene Sean Durkin's impressive debut feature centers on a young woman freshly escaped from a cult commune to her older sister's lake house, but is, more broadly, a dreamy meditation on the unshakability of the past within the human mind: how the people and places and moments we've known inevitably color our perception of the present--a sort of nightmare version of the Beatles' "In My Life," if you will. Elizabeth Olsen (younger sister to Mary-Kate and Ashley, but resembling in voice and presence the disaffected Scarlett Johansson of Ghost World and Lost In Translation) provides precisely the right kind of hazy, damaged, restrained yet emotionally raw turn as the titular heroine; if her performance had been remotely off the mark, Durkin's film simply wouldn't work. John Hawkes is likewise perfectly cast as the creepy, mercurial cult leader who haunts Martha's psyche. Speaking of Hawkes, Martha Marcy May Marlene follows last year's Winter's Bone in making a compelling argument for a new, reinvigorated American independent cinema that is refreshingly far from the quirky-snarky territory of Amerindies' past.

No One Killed Jessica For a viewer like myself, conditioned to the various incarnations of international festival-style (e.g., art-house) cinema, the most jarring moviegoing experience can often come in the form of an unabashedly commercial foreign movie. Raj Kumar Gupta's fictionalized take on the notorious Jessica Lall murder case feels formally alien to me--partly for the reason mentioned above and partly because my familiarity with Bollywood cinema is woefully limited--and my reaction should thus be taken with a grain of salt. The slick look and fast-paced rhythm of the film feel similar in ways to current Hollywood movies (in particular, stuff like Crash and Babel), but the on-the-nose writing, the histrionic style of acting, and the use of the weepy score registered as closer in spirit to the WWII-era Hollywood melodrama. Maybe this is how most Bollywood films feel? I really don't know. Still, I couldn't help but find the glossy form, with its oddly jokey script and abrupt use of dance and hard rock tunes on the soundtrack, disconcertingly crass in conjunction with the sad subject matter.

This Is Not a Film I was optimistically waiting for a truly galvanizing film-event at this year's VIFF--something along the lines of last year's Karamay or VIFF '07's Redacted, movies that (for this viewer anyway) felt instantly like game-changers. On the second-to-last day of this year's fest, that wish was granted in the form of Jafar Panahi and Mojtaba Mirahmasb's This Is Not a Film. Deceptively simple (in form and concept), the film (or non-film) is ultimately one of modern moviemaking's most thoughtful and provocative considerations of the deeply entangled, indeed inextricable personal and political dimensions of creating art. To be sure, Panahi's situation--sentenced to a six-year prison term that, in the film, he's attempting to appeal and banned from directing films for twenty years as a consequence of his involvement in the protests against Ahmadinejad's rigged reelection--is an extreme case, but the implications of This Is Not a Film extend beyond its Iranian context, as Panahi reflects on the director's relationship to, and "directing" of, his actors; the differences between "telling" a film and "making" one; and (necessarily indirectly) the moral-political responsibility inherent in making movies. Despite the dire circumstances of its creation, Panahi's film (with invaluable assistance by friend and fellow filmmaker Mirtahmasb) is as funny and vibrant as it is despairing and sad, and as triumphantly inventive as it is limited by its specific constraints. Brilliantly straddling the blurry line between spontaneous documentation and scripted narrative, This Is Not a Film is the very definition of a sui generis masterpiece.

The Turin Horse Setting aside issues of time-commitment (watching Satantango start to finish requires nearly one-third of a day), I would argue that Bela Tarr's supposed swansong is his most difficult film. Difficult--that is to say, it was considerably tougher for me to find a personal point-of-entry here than it was for Satantango, Werckmeister Harmonies, and Tarr's other earlier films--but not impenetrable, and far from unpleasurable. In fact, once I'd adapted to the fact that The Turin Horse's doom-laden narrative consists almost exclusively of a pattern of repetitions and occasional, ominously suggestive deviations (with these deviations essentially constituting the "arc")--a signature Tarr strategy here rigorously intensified to its apotheosis--I found the film to be among Tarr's most hypnotic and powerful. That said, I'm envious of Jonathan Rosenbaum, who mentions having attended three separate festival screenings of The Turin Horse in his superb Film Comment piece on the film. Of all the films I saw at this year's VIFF, this is the one I most wish I could've caught twice (or more). I'm already crossing my fingers that it will reappear in these parts sometime soon.

VIFF, Part 2: Good Men, Good Women

Once Upon a Time in Anatolia On the one hand, seeing Nuri Bilge Ceylan's sprawling, elusive new film in the late-night festival slot, through blood-shot eyes, seated in the extreme front right of a sold-out theater, and immediately following Ashgar Farhadi's devastating A Separation (see below) may not be the ideal vantage point from which to evaluate and discuss this strange and captivating movie; to be sure, I hope to see it again soon as an evening's main course. On the other hand, few films come to mind that lend themselves so naturally to nocturnal, and even hazy, sleep-deprived, viewing as does this long night's journey into day. Fields of wheat lit brilliant gold by the headlights of cars meandering through the pitch-dark rural night; drowsy, funny, irritable conversations that likewise zig and zag along unsure trajectories; the blurry divide between fact and fable, by turns, compressing and expanding as the sun begins to rise over the Turkish countryside--these are some of the rich ingredients that constitute Ceylan's dazzling anti-epic. To argue that Once Upon a Time in Anatolia is finally less than the sum of these parts--which may or may not be true--is, either way, to miss the point entirely.

Quattro Hong Kong 2 The MVP of this Hong Kong Film Festival-commissioned shorts collection is Open Verdict by Ho Yuhang (director of the superb, and inexplicably under-mentioned, feature At the End of the Daybreak). Shot in the smoky black and white of early Jim Jarmusch, and possessing a similarly droll sense of (visual and verbal) humor, Ho's film is a sly and playful exercise in the negotiation of national and ethnic identification in contemporary East Asia. As a Malaysian national of Chinese descent, Ho joked in his post-screening Q&A about how in Hong Kong he is typically referred to as a Malay, a term that more accurately describes Malaysia's aboriginal population. This general point regarding fuzzy trans-cultural misconceptions is clearly wired into the DNA of his story of an illegal snake-smuggling operation and the customs officers diligently, if haplessly, trying to infiltrate it. As for the the other three offerings: Apichatpong's entry, M Hotel, in which two young men sit on a hotel balcony having an unintelligible (and unsubtitled) conversation that sounds as if it were recorded underwater, is certainly interesting but essential only for "Joe" die-hards; Stanley Kwan's fine if forgettable 13 Minutes in the Life Of... charts the titular passage of time as a bus travels from the airport into the city; Brillante Mendoza's lead-off Purple, hampered by awkwardly phrased English-language voice-over work that spoils its modest verite charms, is the only dud of the bunch.

A Separation Viewed within the context of Jafar Panahi's purposefully titled This Is Not a Film (which I'll be seeing, and reporting back on, next week) and last month's arrest of six more Iranian filmmakers on "espionage" charges, Ashgar Farhadi's ferociously powerful film proves that the Iranian filmic renaissance has not yet been quashed--despite the relentless efforts of the Ahmadinejad regime. It also marks Farhadi as a major talent in contemporary cinema. As an intimate portrait of a troubled relationship (or, really, a pair of them), A Separation succeeds brilliantly where last year's Certified Copy--for which Iran's greatest director took a holiday in Tuscany--frustrates or falls flat. But the genius of Farhadi's film is how it plays equally well as an intense domestic drama (the closest thing in Iranian cinema to Cassavetes?), as a broader commentary on gender-based gaps in communication and social experience, or as a sharp, political study of the problematic coexistence of bourgeois secularism and lower-class religious fundamentalism in today's Iran. Farhadi weaves these (interdependent) discursive streams together seamlessly, leaving any number of interpretative possibilities on the table once the credits begin to roll. [Speaking of which: do not exit the theater until the screen goes black.]

A Simple Life Speaking briefly with the reviewer Robert Koehler after Ann Hui's latest, he made favorable comparisons to Ozu and Renoir. And that's hardly hyperbole. A Simple Life is one of the great family portraits--even if the film centers not on blood relatives but on the bond between a maid and her employer--in recent cinema. Hui's film is fondly affectionate and compassionate while deftly eschewing tacky sentiment; formally smart (shot by the always terrific Yu Lik-wai) but never showy or stylistically distracting; and as warmly funny as it is moving. Deannie Yip--who snagged the Best Actress prize in Venice--delivers what I expect to be the best performance I'll see at this year's fest, but a never-better Andy Lau is her pitch-perfect match.

A Time to Love Another Asian film fest-commissioned work (this one via South Korea's Jeonju International Film Festival), A Time to Love combines two medium-length takes on the romance film, both of the awkward-yet-touching variety (think, vaguely: Judd Apatow productions in a Korean setting). Boo Jiyoung's Moonwalk follows a day in the life of a middle-aged woman, killing time before heading in to work a night shift, as her romantic daydreams involving a co-worker intermingle and clash with her dreary, snow-struck reality. Yang Ikjune's Immature focuses on the "accidental" (read: too much booze) relationship formed between a twentysomething music engineer and a precocious schoolgirl, with echoes of Ghost World's Enid and Seymour (for this viewer anyway). Along the way we get damaged Ugg boots, plush cell phone danglers, a three-legged race, statutory rape charges, and a heaping helping of jjamppong.

Once Upon a Time in Anatolia On the one hand, seeing Nuri Bilge Ceylan's sprawling, elusive new film in the late-night festival slot, through blood-shot eyes, seated in the extreme front right of a sold-out theater, and immediately following Ashgar Farhadi's devastating A Separation (see below) may not be the ideal vantage point from which to evaluate and discuss this strange and captivating movie; to be sure, I hope to see it again soon as an evening's main course. On the other hand, few films come to mind that lend themselves so naturally to nocturnal, and even hazy, sleep-deprived, viewing as does this long night's journey into day. Fields of wheat lit brilliant gold by the headlights of cars meandering through the pitch-dark rural night; drowsy, funny, irritable conversations that likewise zig and zag along unsure trajectories; the blurry divide between fact and fable, by turns, compressing and expanding as the sun begins to rise over the Turkish countryside--these are some of the rich ingredients that constitute Ceylan's dazzling anti-epic. To argue that Once Upon a Time in Anatolia is finally less than the sum of these parts--which may or may not be true--is, either way, to miss the point entirely.

Quattro Hong Kong 2 The MVP of this Hong Kong Film Festival-commissioned shorts collection is Open Verdict by Ho Yuhang (director of the superb, and inexplicably under-mentioned, feature At the End of the Daybreak). Shot in the smoky black and white of early Jim Jarmusch, and possessing a similarly droll sense of (visual and verbal) humor, Ho's film is a sly and playful exercise in the negotiation of national and ethnic identification in contemporary East Asia. As a Malaysian national of Chinese descent, Ho joked in his post-screening Q&A about how in Hong Kong he is typically referred to as a Malay, a term that more accurately describes Malaysia's aboriginal population. This general point regarding fuzzy trans-cultural misconceptions is clearly wired into the DNA of his story of an illegal snake-smuggling operation and the customs officers diligently, if haplessly, trying to infiltrate it. As for the the other three offerings: Apichatpong's entry, M Hotel, in which two young men sit on a hotel balcony having an unintelligible (and unsubtitled) conversation that sounds as if it were recorded underwater, is certainly interesting but essential only for "Joe" die-hards; Stanley Kwan's fine if forgettable 13 Minutes in the Life Of... charts the titular passage of time as a bus travels from the airport into the city; Brillante Mendoza's lead-off Purple, hampered by awkwardly phrased English-language voice-over work that spoils its modest verite charms, is the only dud of the bunch.

A Separation Viewed within the context of Jafar Panahi's purposefully titled This Is Not a Film (which I'll be seeing, and reporting back on, next week) and last month's arrest of six more Iranian filmmakers on "espionage" charges, Ashgar Farhadi's ferociously powerful film proves that the Iranian filmic renaissance has not yet been quashed--despite the relentless efforts of the Ahmadinejad regime. It also marks Farhadi as a major talent in contemporary cinema. As an intimate portrait of a troubled relationship (or, really, a pair of them), A Separation succeeds brilliantly where last year's Certified Copy--for which Iran's greatest director took a holiday in Tuscany--frustrates or falls flat. But the genius of Farhadi's film is how it plays equally well as an intense domestic drama (the closest thing in Iranian cinema to Cassavetes?), as a broader commentary on gender-based gaps in communication and social experience, or as a sharp, political study of the problematic coexistence of bourgeois secularism and lower-class religious fundamentalism in today's Iran. Farhadi weaves these (interdependent) discursive streams together seamlessly, leaving any number of interpretative possibilities on the table once the credits begin to roll. [Speaking of which: do not exit the theater until the screen goes black.]

A Simple Life Speaking briefly with the reviewer Robert Koehler after Ann Hui's latest, he made favorable comparisons to Ozu and Renoir. And that's hardly hyperbole. A Simple Life is one of the great family portraits--even if the film centers not on blood relatives but on the bond between a maid and her employer--in recent cinema. Hui's film is fondly affectionate and compassionate while deftly eschewing tacky sentiment; formally smart (shot by the always terrific Yu Lik-wai) but never showy or stylistically distracting; and as warmly funny as it is moving. Deannie Yip--who snagged the Best Actress prize in Venice--delivers what I expect to be the best performance I'll see at this year's fest, but a never-better Andy Lau is her pitch-perfect match.

A Time to Love Another Asian film fest-commissioned work (this one via South Korea's Jeonju International Film Festival), A Time to Love combines two medium-length takes on the romance film, both of the awkward-yet-touching variety (think, vaguely: Judd Apatow productions in a Korean setting). Boo Jiyoung's Moonwalk follows a day in the life of a middle-aged woman, killing time before heading in to work a night shift, as her romantic daydreams involving a co-worker intermingle and clash with her dreary, snow-struck reality. Yang Ikjune's Immature focuses on the "accidental" (read: too much booze) relationship formed between a twentysomething music engineer and a precocious schoolgirl, with echoes of Ghost World's Enid and Seymour (for this viewer anyway). Along the way we get damaged Ugg boots, plush cell phone danglers, a three-legged race, statutory rape charges, and a heaping helping of jjamppong.

VIFF, Part 1: Time + Place

The 30th edition of the Vancouver International Film Festival is underway! Here's my first batch of capsules:

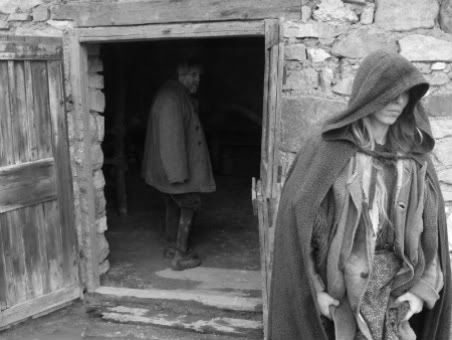

Almayer's Folly Chantal Akerman's adaptation of Joseph Conrad's 1895 novel is a masterpiece of purposefully constructed dissonance: despite the distinctly nineteenth century flavor of the narrative and especially the dialogue, the film is ostensibly set in the present; and while Akerman's vision is wholly (and astonishingly) cinematic, Almayer's Folly is also stubbornly literary, with voice-over narration read presumably straight from the source novel. Here is a story of Western colonialism (specifically, of France in Southeast Asia) compressed to its tragic, fragmentary essence and transplanted in a post-colonial present of wounds still unhealed. In the haunting final shot, the sun washes across the title character's gaunt, angular face before it is again obscured in shadow as he murmurs his regrets--a momentary consideration, and pessimistic rejection, of the possibility of redemption for the post-colonial West.

Dreileben The three films that make up this four and a half hour German omnibus--loosely structured around the occurrence of an escaped criminal stalking around a small town in the (invaluably creepy) Thuringian forest area and guided by the concept of "horizontal" storytelling wherein "the past is washed to the surface"-- vary considerably in both quality and content: The first (and best of the three), Christian Petzold's Beats Being Dead, is, initially, a charmingly intimate look at young love before an unexpected twist changes everything. The second film, Dominik Graf's Don't Follow Me Around, is a sharply comic account of old friends catching back up with one another and reflecting on their shared past. The last entry, Christoph Hocchausler's One Minute of Darkness is both where the madman-on-the-loose yarn comes to the fore (with disappointingly bland results) and where the form of the project, with its intersecting plot points and overlapping timelines, comes to feel rather schematic and overly clever. Taken individually, we've got a very good film, a respectably solid one, and a dull clunker. Yet while, under regular circumstances, two out of three would be fine, Dreileben is cursed by a sense of cohesion that, at its best, calls to mind a sort of German Twin Peaks, but that is ultimately marred by an uninspired final chapter.

Kill List Dreileben suggests the idea of a horror movie, but is, in execution something like anti-horror; the traditional elements of the genre are toyed with in such a way as to intentionally drain them of their potency. Ben Wheatley's Kill List, by contrast, morphs from a bitter domestic drama to a hard-boiled hitman flick into, finally, a legitimately frightening horror movie. The intertitles that announce the next target on the titular itinerary (e.g., "The Priest," "The Librarian," "The M.P.") at first seem superfluous, but pay off near the end, when "The Hunchback" cryptically flashes across the screen. According to the festival guide, Kill List is about "the erosion of the social contract in Britain," and the selection of assassination targets suggests a further subtext in which the Post-Modern Man has violently discarded the institutions of Religion, Academic Knowledge (a stretch, of course, if you know who "The Librarian" is!), Government, and finally the Nuclear Family. That said, this is a film that holds up best as a sly experiment in genre gear-shifting. It tends to buckle under close inspection, so why not leave well enough alone?

Koran by Heart Greg Barker's wonderful documentary centers on the 2010 International Holy Koran Competition, a huge Koran-reciting contest for which talented youths aged seven and up converge on Cairo. The obvious point of comparison here is with the Scripps National Spelling Bee and, in particular, with Jeffrey Blitz's 2002 doc Spellbound. Structurally, the two films are nearly identical: both follow the studying habits and family lives of a few young contestants leading up to the big event. But that's also just about where the similarities end. First, while spelling can be objectively judged for correctness, Koran reciting is intensely subjective and the reciters are evaluated not just for accuracy but for the "beauty" and "spirit" of their delivery. On top of this, many of the kids arriving in Egypt--from points as far afield as Maldives, Senegal, and Italy--do not speak Arabic, despite having memorized the Koran; a boy from Tajikstan, for instance, awes the judges with his "angelic" recitation, but he can neither understand Arabic nor (it is later revealed to the audience) read or write in his country's official language. In capturing these stories as they play out, Barker is vividly presenting the conflict between moderate Islam and more extreme fundamentalist interpretations, and thus considering higher cultural stakes than simply who will win the big competition. Koran by Heart, however, is never didactic or judgmental. Instead, it's very funny, genuinely touching, and uncommonly humane.

The Mill and the Cross Lech Majewski's dramatic recreation of Bruegel's 1564 painting, The Way to Cavalry, could've been a masterwork on the level of Sokurov's Russian Ark. For the first twenty minutes or so I was convinced it would be, as an art-historical world meticulously attuned to the details and rhythms of sixteenth century Flanders awakens to life in a way the distant past is so rarely able to come across on screen. Then, Majewski imposes a completely unnecessary, half-realized plot and some dubious Art History 101 dialogue between Rutger Hauer's Bruegel and a wealthy patron played by Michael York. Worse yet is the voice-over narration Majewski supplies Charlotte Rampling's mother Mary figure, in which she repeats slight variations on the line "I just don't understand..." over and over again. As one of the most visually inventive films of the digital era, The Mill and the Cross is indeed a must-see, but it's nearly as frustrating for its deficiencies as it is astonishing for its strengths.

Year without a Summer Tan Chui Mui's follow-up to her VIFF '07 highlight, Love Conquers All, is at least as accomplished, albeit even more restrained in its minimalist storytelling. The film, set in rural coastal Malaysia, focuses on the characters of Ali and Azam, while weaving back and forth between their friendship as boys and as adult men. Here, Tan is clearly drawing on the work of Southeast Asian cinema's most celebrated current practitioner. But rather than openly engaging with the mythological-supernatural dimension on screen the way Apichatpong does, this element is discussed matter-of-factly by characters, feels inextricably woven into the fabric of everyday life, and its possibility is always suggested just beyond the borders of the frame. Year Without a Summer is as lovely and, at times, hypnotic to watch as it is difficult to write about in a way that conveys some of its delicate, subtle charms; see it by all means.

The 30th edition of the Vancouver International Film Festival is underway! Here's my first batch of capsules:

Almayer's Folly Chantal Akerman's adaptation of Joseph Conrad's 1895 novel is a masterpiece of purposefully constructed dissonance: despite the distinctly nineteenth century flavor of the narrative and especially the dialogue, the film is ostensibly set in the present; and while Akerman's vision is wholly (and astonishingly) cinematic, Almayer's Folly is also stubbornly literary, with voice-over narration read presumably straight from the source novel. Here is a story of Western colonialism (specifically, of France in Southeast Asia) compressed to its tragic, fragmentary essence and transplanted in a post-colonial present of wounds still unhealed. In the haunting final shot, the sun washes across the title character's gaunt, angular face before it is again obscured in shadow as he murmurs his regrets--a momentary consideration, and pessimistic rejection, of the possibility of redemption for the post-colonial West.

Dreileben The three films that make up this four and a half hour German omnibus--loosely structured around the occurrence of an escaped criminal stalking around a small town in the (invaluably creepy) Thuringian forest area and guided by the concept of "horizontal" storytelling wherein "the past is washed to the surface"-- vary considerably in both quality and content: The first (and best of the three), Christian Petzold's Beats Being Dead, is, initially, a charmingly intimate look at young love before an unexpected twist changes everything. The second film, Dominik Graf's Don't Follow Me Around, is a sharply comic account of old friends catching back up with one another and reflecting on their shared past. The last entry, Christoph Hocchausler's One Minute of Darkness is both where the madman-on-the-loose yarn comes to the fore (with disappointingly bland results) and where the form of the project, with its intersecting plot points and overlapping timelines, comes to feel rather schematic and overly clever. Taken individually, we've got a very good film, a respectably solid one, and a dull clunker. Yet while, under regular circumstances, two out of three would be fine, Dreileben is cursed by a sense of cohesion that, at its best, calls to mind a sort of German Twin Peaks, but that is ultimately marred by an uninspired final chapter.

Kill List Dreileben suggests the idea of a horror movie, but is, in execution something like anti-horror; the traditional elements of the genre are toyed with in such a way as to intentionally drain them of their potency. Ben Wheatley's Kill List, by contrast, morphs from a bitter domestic drama to a hard-boiled hitman flick into, finally, a legitimately frightening horror movie. The intertitles that announce the next target on the titular itinerary (e.g., "The Priest," "The Librarian," "The M.P.") at first seem superfluous, but pay off near the end, when "The Hunchback" cryptically flashes across the screen. According to the festival guide, Kill List is about "the erosion of the social contract in Britain," and the selection of assassination targets suggests a further subtext in which the Post-Modern Man has violently discarded the institutions of Religion, Academic Knowledge (a stretch, of course, if you know who "The Librarian" is!), Government, and finally the Nuclear Family. That said, this is a film that holds up best as a sly experiment in genre gear-shifting. It tends to buckle under close inspection, so why not leave well enough alone?

Koran by Heart Greg Barker's wonderful documentary centers on the 2010 International Holy Koran Competition, a huge Koran-reciting contest for which talented youths aged seven and up converge on Cairo. The obvious point of comparison here is with the Scripps National Spelling Bee and, in particular, with Jeffrey Blitz's 2002 doc Spellbound. Structurally, the two films are nearly identical: both follow the studying habits and family lives of a few young contestants leading up to the big event. But that's also just about where the similarities end. First, while spelling can be objectively judged for correctness, Koran reciting is intensely subjective and the reciters are evaluated not just for accuracy but for the "beauty" and "spirit" of their delivery. On top of this, many of the kids arriving in Egypt--from points as far afield as Maldives, Senegal, and Italy--do not speak Arabic, despite having memorized the Koran; a boy from Tajikstan, for instance, awes the judges with his "angelic" recitation, but he can neither understand Arabic nor (it is later revealed to the audience) read or write in his country's official language. In capturing these stories as they play out, Barker is vividly presenting the conflict between moderate Islam and more extreme fundamentalist interpretations, and thus considering higher cultural stakes than simply who will win the big competition. Koran by Heart, however, is never didactic or judgmental. Instead, it's very funny, genuinely touching, and uncommonly humane.

The Mill and the Cross Lech Majewski's dramatic recreation of Bruegel's 1564 painting, The Way to Cavalry, could've been a masterwork on the level of Sokurov's Russian Ark. For the first twenty minutes or so I was convinced it would be, as an art-historical world meticulously attuned to the details and rhythms of sixteenth century Flanders awakens to life in a way the distant past is so rarely able to come across on screen. Then, Majewski imposes a completely unnecessary, half-realized plot and some dubious Art History 101 dialogue between Rutger Hauer's Bruegel and a wealthy patron played by Michael York. Worse yet is the voice-over narration Majewski supplies Charlotte Rampling's mother Mary figure, in which she repeats slight variations on the line "I just don't understand..." over and over again. As one of the most visually inventive films of the digital era, The Mill and the Cross is indeed a must-see, but it's nearly as frustrating for its deficiencies as it is astonishing for its strengths.

Year without a Summer Tan Chui Mui's follow-up to her VIFF '07 highlight, Love Conquers All, is at least as accomplished, albeit even more restrained in its minimalist storytelling. The film, set in rural coastal Malaysia, focuses on the characters of Ali and Azam, while weaving back and forth between their friendship as boys and as adult men. Here, Tan is clearly drawing on the work of Southeast Asian cinema's most celebrated current practitioner. But rather than openly engaging with the mythological-supernatural dimension on screen the way Apichatpong does, this element is discussed matter-of-factly by characters, feels inextricably woven into the fabric of everyday life, and its possibility is always suggested just beyond the borders of the frame. Year Without a Summer is as lovely and, at times, hypnotic to watch as it is difficult to write about in a way that conveys some of its delicate, subtle charms; see it by all means.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)