Clear History: Cinemas Unfinished or Otherwise

Below is a short article I contributed to a new local film journal,

The Parallax. If you're around Vancouver, the debut issue--which also features thoughtful considerations of D.W. Griffith's

Broken Blossoms and the films of James Gray, among other strong work--can be found at the

Pacific Cinematheque and at the

Vancity Theatre. If not, you can download it

here.

-

Originally, I thought that the lights went out in a movie theatre so that we could see the images on the screen better. Then I looked a little closer at the audience settling comfortably into the seats and saw that there was a much more important reason: the darkness allowed the members of the audience to isolate themselves from others and to be alone. They were both with others and distant from them. When we reveal a film's world to the members of an audience, they each learn to create their own world through the wealth of their own experience.

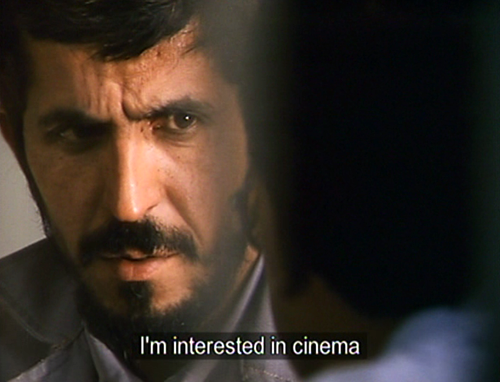

The above is taken from the beginning of an essay by Abbas Kiarostami. Its title is "An Unfinished Cinema"; it was written in 1995 to commemorate cinema's first full century and was distributed at the Odeon Theatre in Paris. In the piece, Kiarostami discusses his reliance on "creative intervention" as a director and calls for a "half-created cinema...that gains completion through the creative spirit of the audience." He concludes by noting that "for one hundred years, cinema has belonged to the filmmaker. Let us hope that now the time has come for us to implicate the audience in its second century."

It's a provocative, perhaps overly theoretical text, on the other hand; for instance, haven't filmmakers from cinema's first century, from Bresson to Pasolini to Kiarostami himself in such films as 1990's

Close-Up or his "Earthquake Trilogy" (

Where Is the Friends House? [1987],

Life and Nothing More... [1991],

Through the Olive Trees [1994]), implicated their audience, demanded a degree of personal, cerebral leg-work to "complete" what's on the screen? Kiarostami's broad strokes seem to paint auteurist cinema as a hermetically sealed-off and fatally solipsistic landscape, turned barren from a lack of fresh oxygen. At the same time, his concession that "it is a fact that films without a story are not very popular with audiences..." refutes any claim to a populism his heady, elusive films had already amply rejected.

Such criticisms of Kiarostami's willful provocations notwithstanding, the essay, written on the cusp of the so-called "digital revolution," does feel curiously prophetic. It's not, of course, like the new technology we've become familiar with in the decade and a half since "An Unfinished Cinema"'s publication was crafted directly for the purposes of remaking or democratizing a medium now so often regarded as hopelessly twentieth century. Rather, that rapidly evolving technology has changed the way we communicate, the way he spend our leisure time, the way we get our news and information; that it's also changed the art-form heretofore known often as film as well as the ways we experience movies seems mostly incidental.

Yet as much as Kiarostami's essay seems, at first glance, to signal the sort of cinematic sea change we've witnessed in the new millennium, have these innovations finally served to make movies more open-ended and "unfinished"? Certainly the technology itself seems dizzyingly ever-evolving, as the eye-popping techniques of just two or three years ago now appear dated--another statement that extends well beyond the increasingly faintly demarcated terrain of cinema. But does wearing a pair of plastic glasses to create a 3-D effect actually qualify as implicating the audience? And while the relative cheapness of digital video has allowed an unprecedented number of would-be auteurs to enter the arena, is the work they're creating as expansively democratic as the economic or material circumstances they've benefited from?

These questions beg more questions still: Is a word like "film" still applicable when a movie has been shot digitally, or when it's being projected that way in a theatre? This generalized misnomer feels almost comparable to one asking for "a Coke," but meaning (and correctly receiving), say, Dr. Pepper or Sprite or ginger ale. Which is to say, do such distinctions even matter to viewers who aren't either industry specialists or nitpicking cinephiles? Certainly, the quality of the movie-watching experience seems to matter to a lot of people, given the popularity of Blu-Ray and the proliferation of massive high-definition televisions and consumer-grade digital home projection.

Yet at the same time, more and more movies are also being viewed on laptops and cellular phone screens. Forget celluloid versus digital arguments: does it even still count as "watching a movie" in any traditional sense when, instead of Kiarostami's hypothetical darkened theatre, the images are flickering across a screen that fits comfortably in your pocket while you ride the bus or the subway? The musings of wiser commentators than myself suggest that everything in the second decade of the new millennium--from where we live and work to what we eat and drink to how we consume media and entertainment--is an extension of "lifestyle." In this view, cinema is, at best, a disposable topic of online conversation, roughly as important, as, say, whether one prefers Macs to PCs, rides a bike to work or drives their car.

The ubiquity of 3-D aside, Hollywood has changed remarkably little alongside these significant cultural shifts. Movies like

Avatar, the

Harry Potter and

Twilight films, and Pixar's annual efforts have earned their studios handsome sums of money, so why fix what's not broken? That's over-simplifying the state of contemporary mainstream movie-making, to be sure, but independent (or, really, quasi- or pseduo-independent) film has, for better or worse, proven far more representative of what has changed since the time of Kiarostami's essay. What's emerged from the margins has been a decidedly mixed bag.

Take, for example, Jonathan Caouette's

Tarnation, Banksy's

Exit Through the Gift Shop, and Henry Joost and Ariel Schulman's

Catfish--each the product of new technology and/or new ways of transmitting information and, to varying degrees, each worthy of praise or interest. But to what extent do these films fulfill Kiarstami's urge for "gaps, empty spaces like a crossword puzzle, voids that it is up to the audience to fill in"?

Tarnation does present Caouette's singular life story as a kind of fragmented mystery, using a Mac computer program to assemble archival footage and pop cultural miscellanea into a vivid collage of trauma. And yet it's at least as impenetrably solipsistic as the auteur-centered work Kiarostami implicitly criticizes as that mode of yesteryear.

Exit Through the Gift Shop is nearly as spry and playful in its study of authenticity in art as Welles's great

F for Fake, but any extent to which it actually implicates the audience depends entirely on that audience's pre-existing familiarity with, or willingness to scour the Internet for, the fuzzy details of its conception.(Ironically, Banksy's film addresses many of the same concerns as Kiarostami's latest,

Certified Copy, but

Exit is slyly self-aware and terrifically funny where

Certified Copy is schematic and muddled.)

Catfish asks some of the same questions, as well, but rather than open-ended or "half-created," Joost and Schulman's film is manipulative and overly slick in its design, if deceptively amateurish in its execution. It's also shot through with a brand of smarmy meanness that's recognizably symptomatic of the Internet Age.

The films of Jia Zhangke and Kelly Reichardt seem to get closer to the kind of cinema Kiarostami is describing. Over the dozen years between 1998's

Xiao Wu and last year's

I Wish I Knew, Jia has consistently blurred the lines between narrative and non-narrative, fiction and documentary, actors and "real-life people" (also a reoccuring Kiarostami preoccupation); at his best, he's able to capture the very cadence of modern life from the vantage point of the world's most populous and rapidly developing nation. Reichardt, meanwhile, is perhaps the brightest light to have emerged this past decade from within the American independent movement. In a film like

Wendy and Lucy, where Reichardt almost completely eschews exposition or telling her audience what to feel, we can, at once, hear the echoes of Bresson and Mizoguchi and see a promising path for the future of cinema. It's a cinema that's personal but not sealed-off, modest but not minor, eager to involve its audience both emotionally and intellectually without neatly categorizing such engagements--and it is exquisitely, invigoratingly unfinished.